Summarize this content to 100 words:

Photo: Curbed; Photos: Getty Images (John Pedin/NY Daily News Archive, Mel Finkelstein/NY Daily News Archive, Bettmann Archive, Dan Cronin/NY Daily News Archive)

The sharpened screwdrivers, memorable and imaginary, tell a lot of the story. Three days before Christmas 1984, Bernhard Goetz, a 37-year-old electrical engineer living on 14th Street, got on a downtown 2 train. A couple of years earlier, he’d been mugged, and he’d subsequently gotten himself an unlicensed pistol, which he carried, concealed, that day on the subway. Four teenagers were in the same car, headed to a video arcade to jimmy open the coin boxes, which is why two of them had screwdrivers zippered up in their coat pockets. They were, witnesses said, rowdy, aggressive, intrusive. One of them asked Goetz for $5, and the story (not to mention the subsequent trial) turned on whether it was a panhandling request with a little edge or an attempted robbery by threat of force. There were about twenty other passengers in the car, so the latter seems unlikely, but this was 1984, the city was in its peak violent-crime years, muggings of all kinds were rampant, and people lived behind triple deadbolts at home and in a state of high alert when they went out. A lot of New Yorkers were on edge, and Goetz was an edgy character to begin with.

He didn’t give them the $5. Instead Goetz pulled out his gun and shot them, including one of the four who (although the defense lawyers later argued otherwise) was sitting apart from the others and had not confronted him. Four guys, five shots, the last one fired after Goetz sneered, “You don’t look so bad, here’s another.” None of the four was killed; Darrell Cabey, the 18-year-old he’d shot at twice, was paralyzed and mentally incapacitated. The “sharpened screwdrivers” entered the tabloids almost immediately and never left, cited as evidence of the young men’s potential for menace. In fact, they hadn’t been brandished, Goetz didn’t know the men were carrying them, and they hadn’t been sharpened at all. What they were guilty of, that day at least, was looking like young toughs, noisy and demanding and above all Black.

Two books, just out in a head-to-head release, present anew the story of the Goetz shooting. Five Bullets is by Elliot Williams, a CNN legal analyst and a former prosecutor; Fear and Fury is by Heather Ann Thompson, a historian whose previous book about the Attica uprising won the Pulitzer Prize. Both lean heavily on recapping Goetz’s long and winding trial, and both agree that it exposed the widening, hardening division that now dominates our politics. It was a classic fringe case, the kind of news story that uncorks endless opinionizing on talk radio and at dinner tables — was Goetz defending himself? Was he looking for a fight? Did they get what was coming to them? Did he shoot mostly because they were Black? Who was the real victim here? — and support for Goetz varied among socioeconomic and ethnic groups but was middling with most. A poll a couple of months after the shooting found that 57 percent of New Yorkers thought he was acting in the right, and when a Post reporter interviewed him in his local coffee shop, people paused for autographs. Support for him didn’t break entirely in the expected political ways: The Village Voice, startlingly, ran a story by Pete Hamill in support of Goetz. (“There were really five victims.”) By contrast, Jimmy Breslin of the Daily News, a paper that was otherwise starting to tilt rightward, wrote, “The bottom line… is that people are rejoicing over a 19-year-old kid who will be in a wheelchair for a lifetime. I’m sorry, include me out.”

Public opinion shifted somewhat — but only somewhat — as Goetz’s racial attitudes came out. He was white and affluent, and it soon came out that he had freely used the n-word in the past. He also said in a taped confession that he had shot the first of the young men not out of fear but in retribution, after he saw “the smile on his face” and “the shine in his eyes.” He was clear: “I wanted to kill those guys. I wanted to maim those guys … If I had more bullets I would have shot them all again and again.” Newsday’s Les Payne, among many others, observed that if the shooter had been a Black man and his teenage victims white, the public response would almost surely have been different.

The trial was a madly raucous media event, requiring many weeks and a sequestered jury. It seems hard to fathom today, but Goetz was convicted only for carrying an unlicensed handgun and sentenced to eight months, with acquittals for attempted murder and the rest of the charges. Most of the key moments in the trial had swung toward the defense. One of the shooting victims, James Ramseur, had been subsequently arrested for a violent crime, and when the prosecutors put him on the stand—a risky move—he handled the questioning badly, shutting down and turning hostile, leaving the impression that he was a rough and unmanageable character. A live-action re-enactment aboard an actual subway car, some of which may have ben of questionable accuracy, presented the image of a man surrounded in close quarters by thugs, unable to escape as he was hounded. (The defense had recruited four of Curtis Sliwa’s Guardian Angels, all Black, all buff and tough-looking, for the staging.) Twist, zip, wriggle, and Goetz’s lawyers found just enough legal slack in the word “reasonable”—as in, was it reasonable for him to respond out of fear—to compel the jury to acquit.

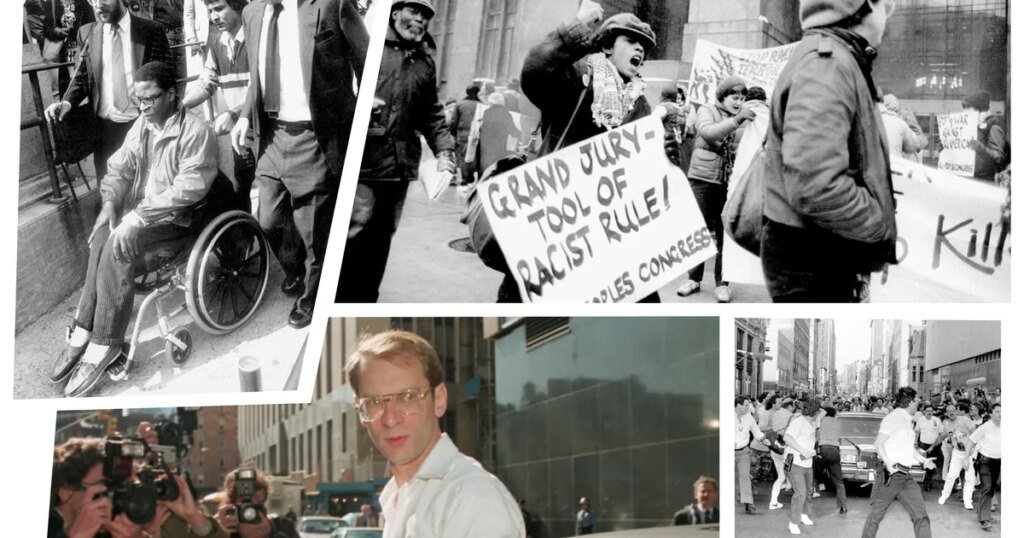

Darrell Cabey leaving Bronx County Courthouse with his attorneys

Photo: John Pedin/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images

Later on, Cabey—who is reportedly still alive, though not well—won a civil judgment of $43 million from Goetz, who declared bankruptcy and never gave him a cent. The other three young men went back, to various degrees, into the woes that often drag down underclass existence: drug use, small-time crime, stints in jail. Two have since died, Ramseur by probable suicide. The third, Troy Canty, is said to be living on the straight and narrow, and keeps out of the press. Goetz, now 78, is defiant and mouthy as ever (just recently, he told off a New York Times reporter who called him for a comment). Forty-one years ago, he was on the front page of the Daily News saying “I’m sorry, but it had to be done”; the other day, he told that Times reporter, “The important thing is I shot the right guys.”

Williams’s book, unsurprisingly given his training, goes in hard on the lawyers’ respective gambits, and he’s good at giving the reader mini law-school lessons, clarifying for example the significant difference between motive and intent. He’s also Black and from Brooklyn and works in TV, which likely accounts for his well-tuned antennae for the overheated madness that was the 1980s New York City news environment. In those years, a miserable and extensive roster of racially inflected deaths, from the Central Park jogger and the Exonerated Five to so many more, dominated local news programs and the tabloids, especially Rupert Murdoch’s Post. Five Bullets is a brisk journalistic trip through that history, and Williams doesn’t shy away from calling Goetz a bigot — which he was, and judging by a phone conversation he had with the author, still is — while being comparatively restrained when it comes to opinionizing. Only here and there do you catch that he still finds the acquittal hard to justify, as most readers probably will.

Thompson’s book aims to be bigger, more sweeping and contextual, and although it takes a while for her literary frame to widen out, she eventually succeeds. Her play-by-play of the trial goes long and drags at times, although I’ll admit that I read Williams’s book first and therefore was already sated with the details when they came up again. Once Thompson gets out past the verdict, though, her analytical engine starts to rev, and she picks up power and speed. Goetz’s move was an early marker of so much: Reagan and the Bushes and their bootstraps-and-faith view of addressing poverty, Rudy Giuliani’s get-tough mayoralty and the mass incarceration that it helped enable, Bill Clinton’s welfare reform, Washington’s increasing disdain for public housing and the people living in it, the mad pushback against even a minimally left-of-center Black president, the rise of the Tea Party and the president it begat. Two of the incident’s characters, Curtis Sliwa and Goetz himself, eventually ran for mayor of New York City, the former seriously (twice) and the latter as a stunt. Surprisingly enough, that era’s most ubiquitous real-estate guy does not seem to have said much on the Goetz matter, but it’s an easy guess which side he came down on. The subtitle of Thompson’s book is “The Reagan Eighties, the Bernie Goetz Shootings, and the Rebirth of White Rage.” If the baldly stated white supremacism that now fills up my X feed is any guide, that reborn entity drank lots of raw milk and grew up with strong bones and teeth.

So did the National Rifle Association, which, both books note, saw an opportunity in the Goetz case and jumped on it. The onetime sportsmen’s association was already moving into its political era of advocating for Second Amendment absolutism, but it tended to stand clear of cities like New York, where anti-gun Democrats ran the show. With the Goetz story the NRA saw a way in for the first time, holding a press conference in New York City to express support for Goetz. A couple of decades’ worth of pressure later, the Supreme Court’s Heller decision affirmed a much broader right to gun ownership than the previous generation’s NRA would have dared thought achievable.

But back to that word reasonable. (Williams titles one of his chapters “Reasonably Reasonable Reasonableness,” which makes the point nicely.) An act like Goetz’s would probably be harder to acquit today. New Yorkers, despite what Tucker Carlson and his ilk would tell you, have much less to fear on the streets and the trains. In 1984, there were about 1,450 murders a year in New York; last year, with 1.3 million more people living here, the total was 305. We also, appropriately, judge users of the n-word more harshly than we used to. (That sentence is itself evidence thereof: In 1984, most news outlets would have quoted Goetz using the word itself.)

These two books intend, as you might expect, to connect the Goetz case to our time, and just this past week the echoes have been deafening. We are absolutely swimming in defenses of violent retribution in the name of civil order and righteousness, not just in cities that are widely perceived as lawless but everywhere. Stand-your-ground laws, the castle doctrine, the very name of the Department of Homeland Security: All are about not just safety but feeling safe, often by detaining or excluding or demonizing entire groups believed to be dangerous — immigrants, Black teens in a mostly white suburb, gangs that are purportedly flooding over the border. Whether a person actually was in danger is only modestly relevant; if he believed he was, that’s enough reason to kill. (Of course it also matters who, in terms of identity and race and wealth, that endangered person is.) Similar rules applied with Jordan Neely, choked to death on a subway train in 2023 by Daniel Penny, a former Marine who said he was afraid of Neely’s erratic and threatening behavior. Penny, too, was acquitted by a jury who decided his actions were reasonable. Just this month, after Renée Good and Alex Pretti were shot dead by federal agents, what was the administration’s stance? They should have behaved; one was armed, even if he didn’t brandish his gun; the shooters feared for their lives. And another talk-radio-caller argument, after Good’s killing: Was the driver looking to run the agent over with her car? If so—and here we go again—I’m sorry, but it had to be done.

Sign Up for the Curbed Newsletter

A daily mix of stories about cities, city life, and our always evolving neighborhoods and skylines.

Vox Media, LLC Terms and Privacy Notice

By submitting your email, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Notice and to receive email correspondence from us.

Related